Let’s begin with a moment of review: Postmodern Art is not inherently evil because the philosophy of Postmodernism isn’t the defining characteristic of Postmodern Art. Postmodern Art is when the primary focus of the artist’s skills is the relationship of the audience to the work of art — as opposed to the other focuses like the quality of the realism of a painting.

When a movie subverts the audience’s expectations, it is being Postmodern (think of that the amazing film No Country for Old Men). When a movie is trying to promote moral or philosophical relativism, it is being Postmodernist (think of Forrest Gump).

Because Postmodern art shares a similar name with the philosophical movement Postmodernism, many have written off any value to be found in Postmodern art. This is a shame because many of the developments in the arts discovered through Postmodern artists are amazing. The Postmodern focus on the audience’s perception reveals a number of false frames that served only to limit how and with what art can be made. Framing is a great term to summarize the focus the Postmodern artist’s focus.

Literal framing? Sometimes.

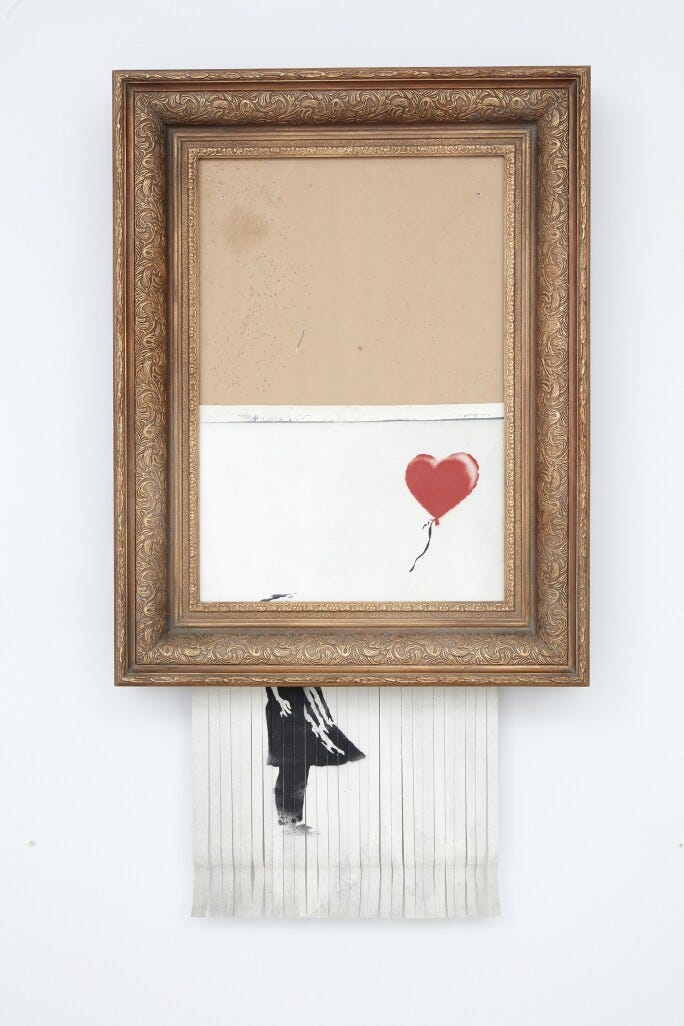

Love is in the Bin, 2018

by Banksy

Banksy manufactured a frame with hidden roller and razors built into it, which then activated when his artwork was sold at auction. The mechanism failed partway through only shredding part of the image. Banksy went to great lengths trying to subvert the auction and upend the monetary value of his artwork. But like Duchamp, he failed. The work was considered even more valuable after the partial destruction.

More commonly, the Postmodern artist is not creating elaborate razor filled frames, rather, is challenging all manner of framing devices. Framing devices are anything which contextualizes how a work of art is viewed. Here are some examples: the wall text at the beginning of an exhibition, the architecture of the gallery, the manner in which the gallery attendants respond to the audience, the way a painting is hung on the wall (imagine a painting hung 30 feet up on a tall wall), or any other “frame.”

Most often the Postmodern artist starts with a question about some sort of framing implementation. A question such as:

What if the standard dimensions of the frame are altered?

What if there is no frame?

What if the walls aren’t white?

What if the work is outside?

What if the work is difficult to see?

What if the work is made of materials we don’t associate with art?

What if the work is temporary?

What is the work isn’t a physical object?

What if the artist doesn’t touch the work with their own hands?

All of these questions take a preconceived notion about art and reconsider whether that notion is necessary for a work to be considered art. For the specific questions listed above, the notions questioned include: the necessity of a frame and its overall decorative qualities, the neutrality of the museum white walls, the value of sterility in the gallery space verses the living outdoors, the need for an artwork to be clear and distinctive, the aesthetic value of costly materials and minerals, the concrete permanence of great artworks, the objective value of the object nature of an artwork, and the importance of the artist’s touch.

These are the same sort of questions Marcel Duchamp was asking when he made his famous piece — Fountain — with which he was attempting to end art making. However, it was Robert Rauschenberg who started making truly interesting artworks in response to these sort of questions. His artwork was not merely destructive anti-art, but artwork that raised thought-provoking questions and revealed ancient influences in all of art.

Monogram, 1955-59

by Robert Rauschenberg

In the 1950s Rauschenberg started making art with all manner of unusual and unexpected materials. In this “painting” a canvas is laid atop casters, on top of which a stuffed Angora goat stands. The goat is intertwined with a painted tire and the goat’s face is smeared in paint. Rauschenberg called this, and other works of a similar technique, Combines. That is, he was combining sculpture and painting.1

You can imagine Rauschenberg asking the question, “what makes a painting different from a sculpture?” It may seem obvious — three dimensions — but after seeing Van Gogh’s heavy brush strokes you cannot argue that paintings are truly flat.

He is even playing with the term Monogram by using it as the title of this strange piece. A monogram is a sort of logo made using only intertwined letter forms. (Think of the “GE” in General Electric of the “LV” for Louis Vuitton.) There are a couple letters included in this artwork, notably “D” and “A,” which might remind us of the artistic movement Duchamp was part of — the Dada. Rauschenberg did not derive the title of the piece from using the Dada letters though, he derived it from the way the goat and tire were intertwined.

What?

Here is a different view:

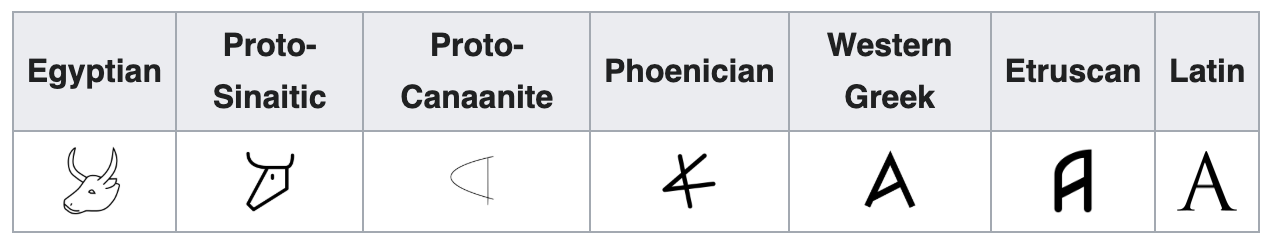

What do a goat and a tire have to do with letterforms? Well, this might be a stretch, but it reminds me that all letter forms were originally pictograms. You know how Egyptian hieroglyphics are pictures of actual things? All letters started this way. Take the letter A. It’s an abstracted image of a bull. It doesn’t look much like that now, but here is the chart showing how it started and what it is now:

Okay, so the goat and the wheel could be seen as inspiration for letter forms in ancient days. What does the origin of letterforms have to do with this crazy collage painting which is obviously a sculpture not a painting?

I think this question really helps us understand my frustration with the Avant-garde argument in particular. Modern and Postmodern artists were not looking and moving forward. They actually, most often, were looking and moving backwards. Back to the roots of art.

Rauschenberg asks: When did we start to think of painting and sculpture as different? Why do we want/need to separate the two mediums? When did a monogram become abstract letter forms instead of physical realities?

I think for many the Combines feel like a chaotic deconstruction. Like these Postmoderns are merely tearing down all the institutions and mediums which culture has painstakingly built over hundreds and thousands of years. This is not the case.

Postmodern art is not deconstructive necessarily, rather it is looking back at the evolution of art to see if there were any missed off-ramps. If the camera brings about the death of painting as we know it, might there have been a different path to take?

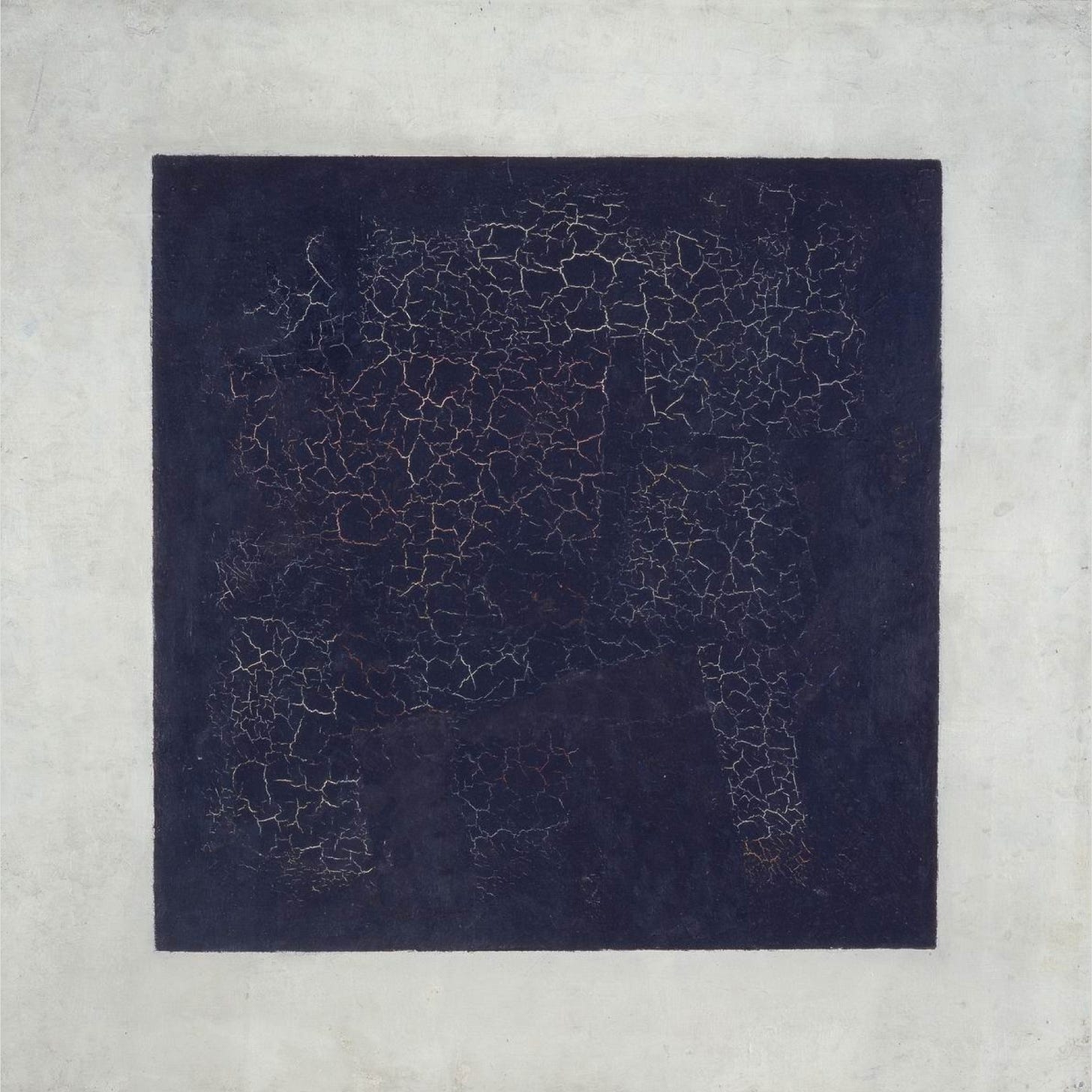

Here, let me prove it. When the Modern abstract artist Kazimir Malevich painted a black square in place of an icon of Christ, many, including Hans Rookmaaker, argued he was stripping God from art:

Black Suprematic Square (1915)

by Kazimir Malevich

This was considered a “new” attack on God, and was only possible due to the atheistic nihilism of the 20th century.

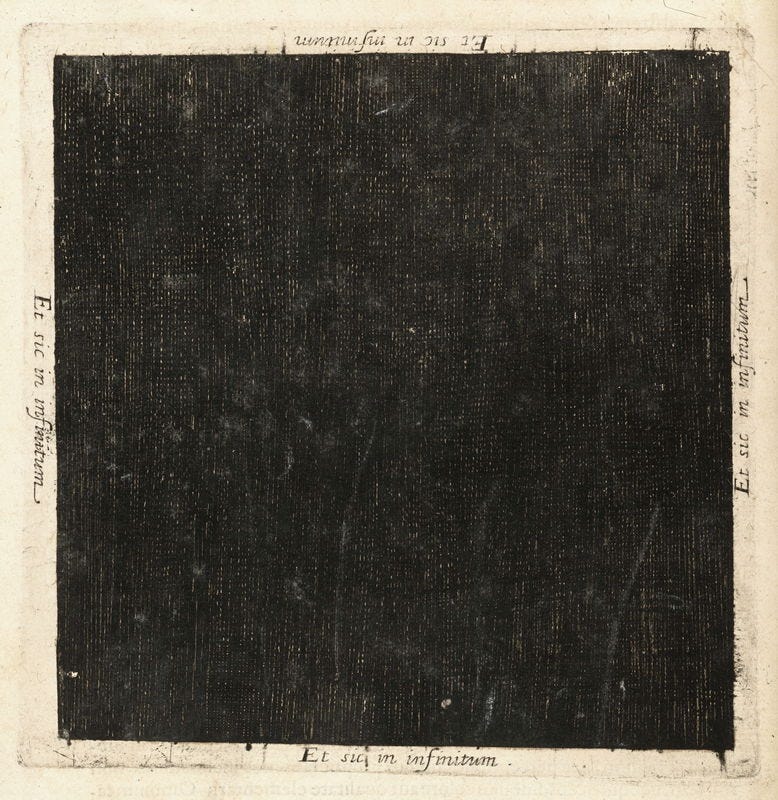

But wait a minute. What is this?

The Nothingness that was Prior to the Universe, 1617

by Robert Fludd

Nearly 300 years before Malevich, an artist who was endeavoring to make diagrams of the philosophical and theological underpinnings of Christian dogma made this image. Malevich is trying to grasp the paradoxical nature of God’s infinity and the reality of the incarnation of Christ. Fludd is trying to grasp how to depict the only “thing” that existed before anything existed — God. Both artists are asking the same question: How do you make an image of an infinite God who exists outside of space and time?

Malevich was not marching forward. He was looking back. The Postmodern artists often have more in common with the medieval artists than they do with the Modern artists.2

The Postmodern questioning of our preconceived notions can certainly lead to dumb and dangerous denials of truth; but they can also reveal how we have pulled the wool over our own eyes with assertions about art that hobble entire mediums. Painting in the 1800s was a very limited medium because its parameters were so restricted by the academy.

The Postmodern movement has freed up what materials artists can use. Reminding artists all manner of materials can be meaningful as art. This leads to urinals, feces, blood, and other banal materials, but it also leads to Andy Goldsworthy. An artist well known for his work with and in natural settings. He takes leaves and rocks and makes them, well, into art. How? Not by grinding them into pigment. (Actually he does do that with some stones but he doesn’t paint with it. He stains puddles with color.) Most often he merely rearranges what he finds in nature. Like this:

Void Series, ca 2001

by Andy Goldsworthy

Questioning the established standards of art in the 20th century allowed an artist like Goldsworthy to explore mundane primal materials. Thank God for he is an artist who is able to find the glory of God in even dying leaves that are blown away a few minutes after the photo. Like grass thrown into the furnace.

If you have time, I highly recommend this documentary on Goldsworthy. While you watch, remember this form of artmaking was only made possible by Duchamp’s misguided notion that art is meaningless. Thank God for his foolhearty attempt to destroy art. For rather than destroying it, he shook off the shackles.

Though technically different from collage (collage is considered two dimensional) the Combines are a form of assemblage (three dimensional collage). Rauschenberg was interested in the power of the word “combine” because it implies a coming together of the mediums of painting and sculpture as opposed to the constructed implications of the word “assemblage” which is related to the word “assemble.”

Yes, I know I have tied the Modern and Postmodern artists together. What I mean is this: The Postmoderns are similar in that they still engage in the splitting and dividing practice of the Modern artists. But thematically, since they are exploring notions of framing, contextualization, and perception, they fall into similar paths medieval artists did. Paths like Malevich and Fludd. But you will see other similarities as well. What are medieval relics but Postmodern ways of framing strange materials so that they are perceived as valuable. Whether the relics are false or not. In fact that fabricator of false relics is most certainly a Postmodern artist.

Re: footnote 1 - thank you for clarifying. That is really interesting.