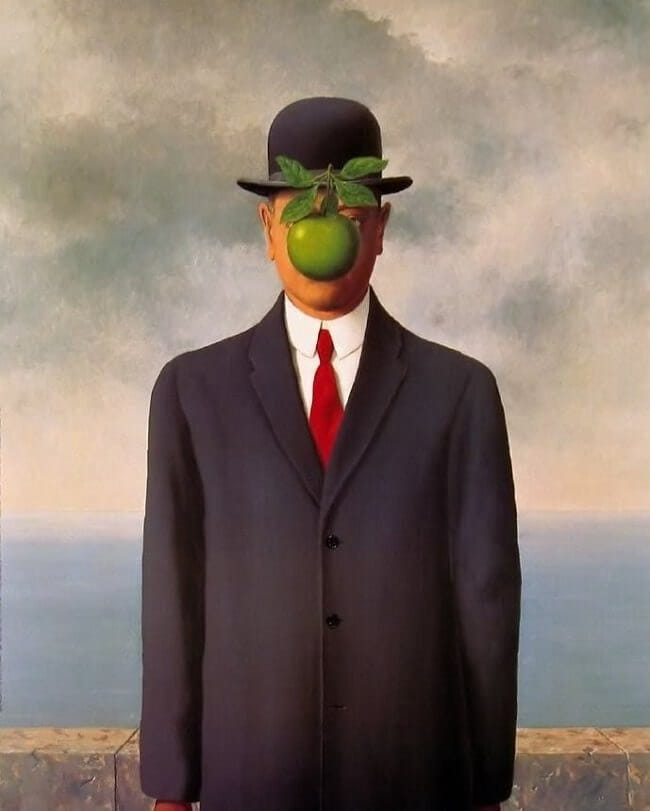

The Son of Man, 1946

by Rene Magritte

I have been pondering my memory of late. Of course some of this preponderance of pondering was triggered by my Do Ho Suh home-making reflection last week. Unfortunately that is not the only motivating factor; a recent tragedy triggered a need to dwell longer within the tent of memory.

A childhood friend sustained a concussion and woke up having lost 11 years of his memory. In that time he had been divorced and remarried, his eldest child had aged from 5 to 16, he and his new wife had children. Yet he does not know who these loved ones are–he can barely recognize his eldest. He woke up to a real-life sci-fi thriller, except there isn’t the distance of a t.v. screen, its palpable and real. It is in your face. It blocks out everything else in their lives. (Like the apple above.)

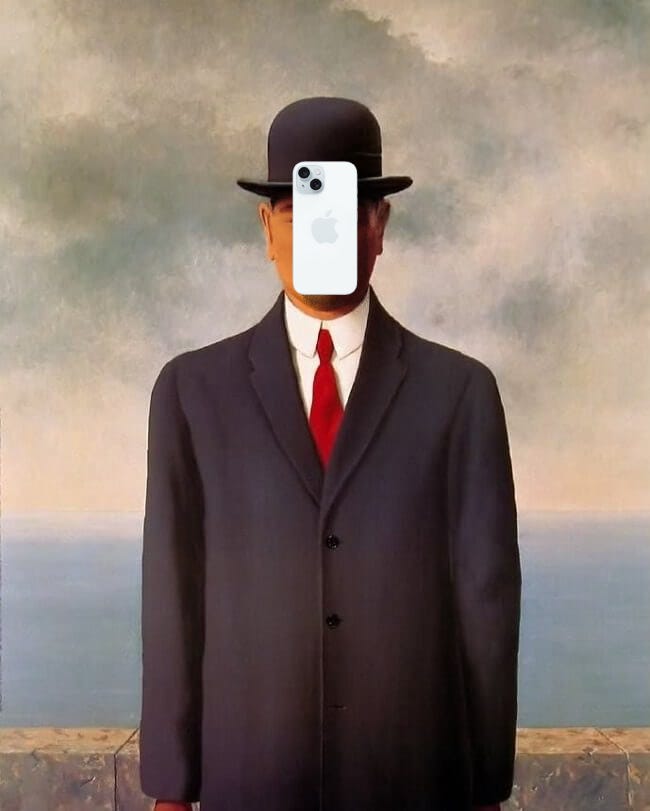

Of course, I wonder what would happen to me if I lost the last 11 years? My wife, Janee, and I have been going through a litany of things we would miss. As we list off milestones and memories, in the age of the attention economy, I cannot help but notice how often I use my digital device to help “aid” my memory. A device that stores my mementos in a digital cloud that allows a sort of nonchalant-unknowing after clicking through an End User License Agreement–without reading it of course. This unknown cloud is accessible with a high-speed internet connection, otherwise all those mementos are just outside my reach.

Perhaps if Magritte were alive today he would repaint the image above with a different apple in front of the face of “The Son of Man.”

I fear losing my memory. But if I want to somehow strengthen it or save it I have to ask; what is memory?

Words are originally pictures of experiences. As in, all words stem from an original cohesive experience that our ancestors encapsulated into a word. They are metaphors. As soon as I start researching the etymology of memory I see it is obviously connected with remembrance. One way of thinking of memory is as “unconscious traces of past conscious experiences.” Our memory is the archive of our past. It is like you have a huge library of past experiences stored on book shelves. When you need to you can step through the stacks and find the name of that-one-guy-who-did-that-one-thing. When we “recall” we are pulling the tomes off the shelves of our memory archive to re-experience them.

So what of those who are suffering like my friend? What of dementia or Alzheimer’s patients? Suffice to say, I have no clue how to help those with medical afflictions.1 If popular film’s have any accuracy, they claim that physical memento’s can help. I have heard several personal anecdotes in this regard as well.

Physical and psychological afflictions aside, art can definitely help the memory of the un-afflicted mind. Look at the word remembrance. “Re,” again. “Member,” a unity of parts. Think, renewing the Sam’s club membership after you let it wane. To re-member is to be rejoined with something of the past. How can art help us be reunited with our former memberships?

One of the old definitions, via the Oxford English Dictionary, mentions a ring of remembrance as, “a device with rings used to prompt the memory.” Art can also function in this manner. It can prompt our memory. If you have read my first depths post my second question to ask yourself as you encounter a work of art is regarding what the artwork reminds you of.2

If objects, both mundane objects and art objects, can trigger our memories how should we capitalize on this trait?

The Death of Socrates, 1787

by Jacques-Louis David

This painting holds a good strategy for how to use objects art and otherwise as memory aids.

First, let me explain the story the painting depicts. Socrates is accused by the city of Athens of “corrupting the youth” with his teachings. He must face exile or death. Socrates chooses death by poison hemlock. Jacques-Louis David captures this moment as he reaches for the poison, to the demise/surprise of his students and followers. But that is only 2/3rds of the painting. The left side is something else. Well, part of the left side. In the background Socrates’ wife is escorted away and a young man cannot watch. But there is another figure dressed in white, like Socrates is dressed.

Facing away, with his head resting on his chest, sits an elder Plato–Socrates’ most well known student. But wait, if he is the student, why does he look older than Socrates? What is happening here? Look on the floor next to Plato. There is a scroll.

He has just read something and is now praying/meditating? I think he is re-membering or re-living the events of his past. The painter understood Plato’s dialogue called The Phaedrus.3 Part of the dialogue famously condemns writing. Plato–through his character of Socrates–says that writing will dull one’s memory. We need to realize that this isn’t a straight forward condemnation of all writing though, because he wrote it down!

Plato goes on to detail how you should write in a way that is encoded so that you are forced to engage with the writing in a process of “remembering.” As in, when you write, bury the lede and make you mind work. Don’t write a list of twelve rules for life or didactic to-does. Write a story. Symbolize a complex and deep truth so that when you read, whether it be a book or a work of visual art, it recalls the experience you want to remember through the activity of engaging the artwork. Write in a manner that there is more left “between the lines” than is written on the lines.

A bit like the Pensieve in Harry Potter I suppose, where the edges of memories are far more important than the focal point. Or, like my good friend Josh wrote about a particular coin in his pocket.4

So how does this painting hide the answer to the question above? How does this painting unlock for us the way to use art as a prompter of memory?

Look back to the painting, at Plato contemplating:

His hands are folded, the scroll is on the floor, as the vivid details from his memory hover behind and around him, his eyes are closed. This is what Plato meant about writing that could aid your memory. Writings are not the only things that do this though. It might be a family photo, it might be a scent, it might be a song on the radio. Find the objects, the mementos, the artworks, the books, the music, the things that put you in a trancelike state of remembrance so deep you look like you are in prayer.

I don’t mean just objects that trigger memories of your own specific past either but larger stories and ideas you value. After all, Plato’s dialogs were most likely a majority fiction. Which means his own art of writing reminded him of more than what happened, but what he thought about what happened.

What are they things you believe fervently and care about deeply? What are the things that if you lost 11 years of memory you would want to be reminded of? Find/make mementos of those most important experiences and values in your life.

For each of us these things will be different. The things you need shoved in front of your nose like Magritte’s “Son of Man,” might be similar to what I need, but I doubt it. They might be expensive works of art or they might be the box set of Calvin and Hobbes.

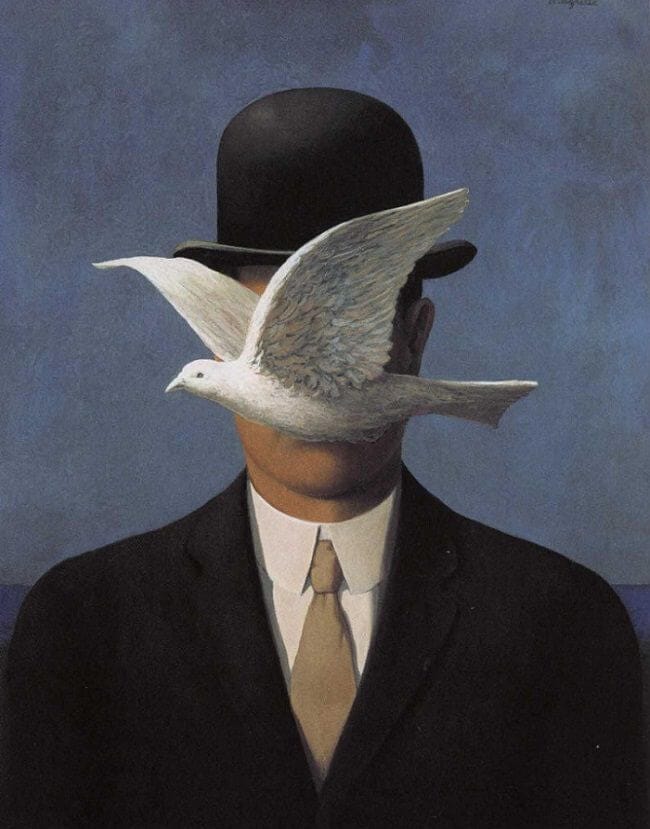

Intentionally setup a place of re-membering and put it in front of your face from time to time.

Man in a Bowler Hat, 1964

by Rene Magritte

Don’t forget those red words in the Gospel of John, “But the Helper, the Holy Spirit, whom the Father will send in my name, he will teach you all things and bring to your remembrance all that I have said to you.” We are meant to remember, so tend the garden of your memory while you can. Fill it not with weeds, but stones and monuments that speak to you, that speak memory5 into you.

P.S. my friend’s memory was restored after fellow Christians laid hands on him and prayed for him. A True re-memberance.

This post will not delve deep into why this is a helpful way to approach art but look forward to a post detailing why I think this is a useful second question to ask yourself when experiencing art of any kind.

I have only met a single Plato scholar (which I have not met many so this might be a condemnation of my own lack of philosophical networking) who knows what The Phaedrus is about. Let’s put it this way, if you think it is about love and sex, then why is there a whole diatribe condemning the practice of writing? That diatribe, delivered to us in the form of writing. For more of my thoughts on this painting and the dialog check out my YT video on the topic.

There is one minor point of contention between Josh and I. That is, his use of the word magic. I don’t disagree with him necessarily, but my agreement hinges on what he means when he says the coin, “is not magic.” I suppose if he means that the power of reminding the coin holds is not the product of an arcane spell, then I would agree. But, the coin does have an actual power that actually splits his consciousness between the present and the past, allowing for a dual experience we call remembering. It has the power to do this on a palpable level. That seems an awful lot like “magic” in a sense. I will cover this more in a future depths post about what I mean when I expand on the third question you should ask about an artwork, “what does a work of art mean?

Nabokov titled his memoir Speak, Memory. I think he knew a bit about The Phaedrus and how to trigger a memory through writing.

I really appreciate the stark point that we so often put “apples” in front of our faces instead of more meaningful reminders.