Note: Substack published this post yesterday before I was done editing it! Something to do with an update and me working offline for a bit. I apologize for the duplicate email but this one has a few edits!

Marshall McLuhan renamed the galaxy we live in the Gutenberg Galaxy after this guy:

Johannes Gutenberg, circa 17th century

by Nicolas de Larmessin

McLuhan was a bit of an odd duck – just check out his strange collage book The Mechanical Bride1 – but he was not denying our place in the heavens like the flat-earthers. He spoke in hyperbole in order to get across a vast metaphor.

The metaphor: that the product of Gutenberg was so fundamentally powerful it changed the nature of where we place ourselves in the universe. What was it that Gutenberg made?

Gutenberg Examining a Page, 1904

in a book by Adele Millicent Smith

The printing press. Specifically, the moveable type printing press. This revolutionized the art of bookmaking and changed our relationship with words. So much so, McLuhan argues, we now live in a galaxy populated by words and books more than anything else. The stars were most useful as navigational reference points. McLuhan’s metaphor links that use to the printed word.

It is a hard to metaphor to argue with when the actions surrounding Elon Musk’s acquisition of Twitter (now X) was spoken of as a fight for free speech. Which, need I remind you, it is not a platform of speech but rather the written word (among other things of course). We conflate the written word with speech because of the power printed words hold. Our world is shaped by words, spoken or written (tweeted or… X’creted? X’ted? X’ecuted?) in a similar way to how our planet was formed from stardust.

This series of Reflections started in response to some common theological concerns surrounding the treachery of images. Concerns that are the most radical when taken to the extremes of iconoclasm. Iconoclastic views are usually held by reformed Christians, ancestors of Martin Luther. In fact, Gutenberg was a good German Lutheran.2 The reformers, most notably John Calvin, emphasized words above images and icons, shifting the way we use language and changing the location of our galaxy.

Why? What’s so special about words that they dominate our world?

Question Mark, 2001

by Richard Artschwager

Words wield the power of naming. Another way of saying this is: words define things. They are like swords that cut the mold from the cheese. Defining one part as mold, the other as ambrosia… err, cheese I mean.

Jesus Appears in the Book of Revelation Holding Seven Stars in His Right Hand and with a Double Edged Sword Coming Out from His Mouth, 1763

by Bernard Picart

This power of words wield is wonderful! Well, it can be wonderful. (See how careful and specific I am trying to be with my words?)3 As with the other artforms I have mused upon, the art of wordsmithing can also be treacherous.

Zat So, 2023

by Ed Ruscha

Yes, it is so. Thanks for asking Ed.

In 1966 an advertisement in the Times-Picayune of New Orleans mentioned a strange tale about the twisting way of words. The tale was that these laudatory words were ascribed to Queen Anne, who was on the throne when the St. Paul’s Cathedral was officially completed:

Queen Anne summed up her feelings in three adjectives: AWFUL, AMUSING, ARTIFICIAL. Sir Christopher was joyous. You see, in 1710 the word awful meant “awe-inspiring,” amusing meant “amazing,” and artificial meant “artistic.”

The meaning of words change over time as the context and way we use them changes. Don’t believe me? Google the history of the word “gay.”

The treachery is not that words change as language changes, its that their communication relies upon context. Words cannot be understood in isolation. They must be contextualized in order for them to be deciphered.

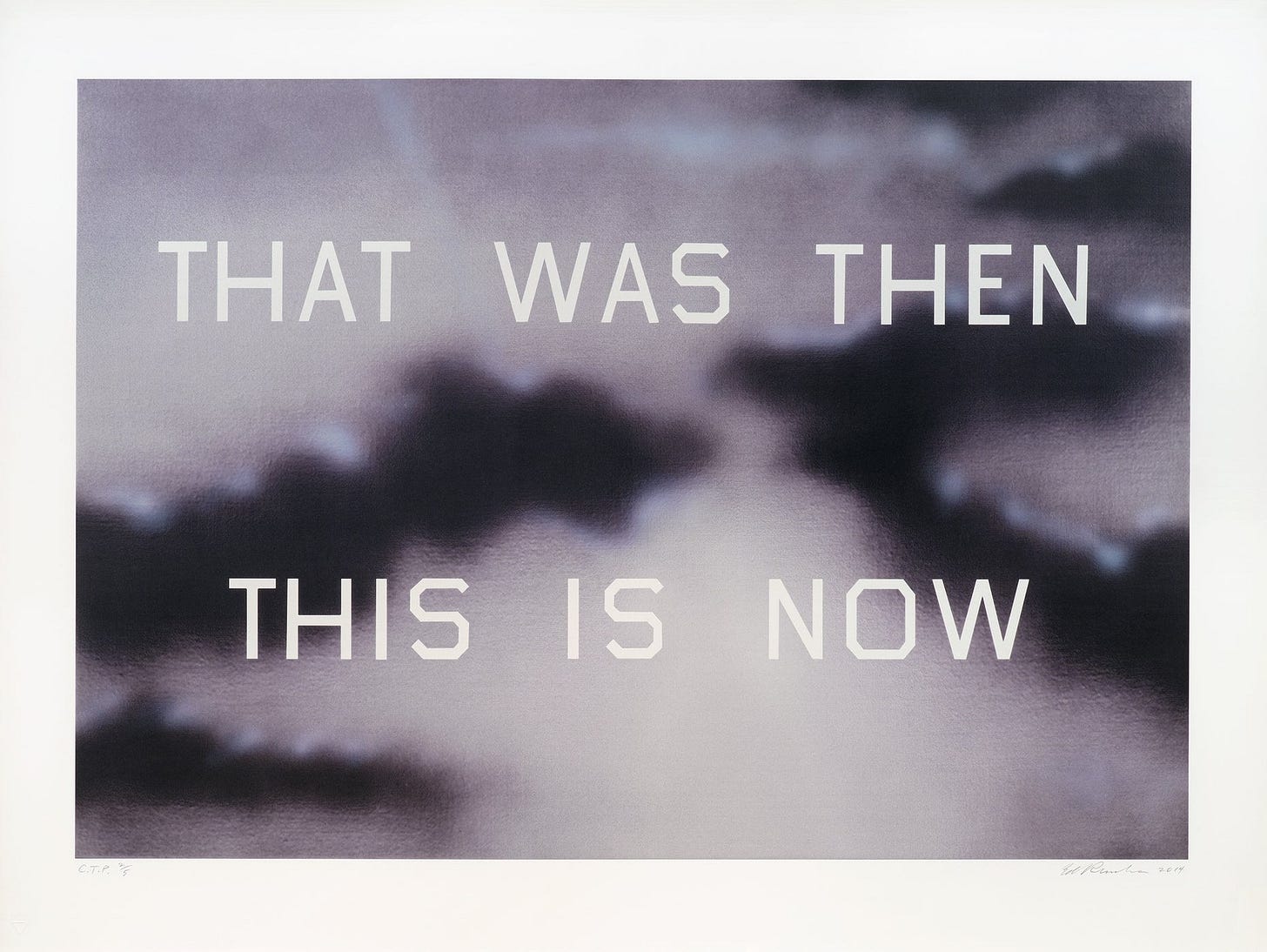

That Was Then This Is Now, 2014

by Ed Ruscha

Words taken out of context are why dictionaries need to list multiple definitions for each word. When I search for the dictionary definition of the word “fire” it gives me 39 distinct definitions. Together these 39 options are trying to encapsulate every single conceivable context in which the word could be used. (From: “Fire!” to, “That’s so fire!” to “You’re fired!” to “Your fire!”)

But there are only so many contexts that one can imagine. The dictionary can only be responsive to the context we humans have already discovered. This means that dictionary definitions simplify words so to cover more contexts. Iain McGilchrist discusses this limitation in his book The Matter with Things:

Language relies on approximation: a language with a word for every distinguishable aspect of the world would not be a language at all. It would be like the map that is the same size as the world it maps. Language always shrinks reality: the one exception to this is poetry, which absolutely depends on ambiguity to escape. Language is a gross approximation – and that's why it works. Yet there exist people who believe that only once a thing is stated in language can it be precise. (Well, I grant you, a map has a precision that life lacks. It's just that that precision has little to do with reality.)

What is McGilchrist after? How does language shrink reality? Some Inuit dialects have over 53 words for snow. Compare that to the few names for snow that most American English speakers have (snow, powder, slush, flakes, and Frosty). Our limited vocabulary binds the way we perceive snow. For example, as I mentioned in my post on gardening, the word “weed” collapses a vast amount of plants into one simplified category – distinctive individual plants become one mass in the vast category of “weed.”

McGilchrist again in The Master and His Emissary:

…words can influence our perceptions. They can interfere with the way in which we perceive colors – and facial expressions, for that matter – suggesting that color words can create new boundaries in color perception, and language can impose a structure on the way we interpret faces. In other words, language is necessary neither for categorization, nor for reasoning, nor for concept formation, nor perception: it does not itself bring the landscape of the world in which we live into being. What it does, rather, is shape that landscape by fixing the ‘counties’ into which we divide it, defining which categories or types of entities we see there - how we carve it up.

Carving again. Like swords.

Words, as defined in dictionaries, produce the illusion of certainty; making us act as if we know, or as if we understand something, completely. Go ask a quantum physicist to define what fire is in as much detail as possible.4 The best words can actually do is gesture at a phenomena in life with metaphors.

A metaphor is something that bridges a gap or “carries things over.” For example, I just used the word understand and you read right by it knowing what it means. Well, what does it mean? To under-stand. To place yourself beneath a thing so that you can see its roots. See? That is a metaphor. When someone says, “I understand,” it is as if they are standing beneath a thing so that they can see where it comes from, where it is rooted. The word “understand” bridges the experience of seeing where a thing is rooted in the ground. It makes think link with just three syllables of sound on eardrum or ink on page or pixel on screen.

The first English dictionary writers understood this. They did not set out to define words, they set out to interpret how words had been used by people. That is, they had to look at what metaphors the words were bringing to mind.5

The iconoclasts like Calvin were rightfully afraid that images and sculptures could be mistaken for the thing they represented. So, they turned to the written word but fell into the treachery of words. Do you see the assumption they made? The assumption is that words don’t represent, they define. An image of God is not God. But is the word “God,” God? How about 1,000 words describing God? Do those words encapsulate God? What about 1,104 pages of words?6 No. They are only partial because, as McGilchrist says, words are inherently approximations. Or, words are approximate definitions at best.

Words, like every art form, can only get us so far. No RE-presentation will every fully present all of the universe and all that is beyond this universe. They can only reveal a small sliver or as Madeleine L’Engle puts it:

…our conscious minds are indeed only the tiny tip of the iceberg which is above the water, and the largest part of ourselves is unseen below the water, below the conscious level, and it is not easy to admit this, to admit it and not fear that large part of ourselves over which we have very little control, but in which lies enormous freedom, and the world of poetry, music, and the region of that deepest and truest prayer which is beyond all our feeble and faltering words. We need the prayers of words, yes; the words are the path to contemplation; but the deepest communion with God is beyond words, on the other side of silence.

Words are worth a lot, but the certainty of the defining power is treacherous. We need to remember that words are much weirder than the dictionary makes them out to be. To that end, don’t try to merely understand the combination of words in this proverb poem in your mind, rather, speak them aloud. Let the words take shape in your mouth and tumble out like sawdust spewing out the back of a saw. (This practice is part of that iceberg floating below the water, the part of your consciousness that cannot be mapped):

Proverbs by Angie Estes Mortise and tenon, tongue and groove, tongue-in-cheek, the tenor holds the note until it dovetails in air like the white kerchief of the Holy Spirit tied around the neck of God in Masaccio's Trinity, the dove more banner than bird, which from the beginning was the word for verb—part sky, part earth, part of speech expressing action, occurrence, existence. It is wonderful, Stein said, the number of mistakes a verb can make. Pardon, scusi, word for word, tell me whether the theory holds and, if so, how we will hold up, hold out, hold on, and then I will hold you to your promise the way the arms of God hold up the cross, which holds up Christ. To have and to hold: hold that thought. Besides being able to be mistaken and to make mistakes verbs can change to look like themselves or to look like something else. The inscription above the skeleton below Christ's feet, for example, says the same holds for you: I was that which you are, and what I am you will be. So much for vers libre. Do you think he looks like himself? they asked, glancing toward his casket. In the hold, in Masaccio's fresco, the grave is a wall with a barrel vault pierced through, deep chamber below a coffered ceiling where God holds forth in rose and black. Behold, I show you a mystery: a ruse is a ruse is a ruse. In Latin, to have verve is to have words. It could be a version, aversion, a verse: please advise. Not much we can know save the redbud, which wears its heart on its leaves.

It is prophetic. I desperately wish he had lived to see the proliferation of the internet.

The first thing he started machine printing was the Bible.

My back is sore from all the patting.

See the film The Professor and the Madman.

The page count of my copy of Calvin’s Institutes.